The first thing that impressed me about the Harry Potter novels was the story; the second thing that impressed me was J.K. Rowling’s use of semicolons. I was happy to see her punctuate closely related independent clauses with a semicolon.

And I have found, when reading some mystery fiction, more semicolons than one would normally encounter in a novel. The first question I ask myself is: Was the author an attorney? Quite often the answer is Yes. Perhaps the legal mind is attracted to the fine distinctions made by semicolons.

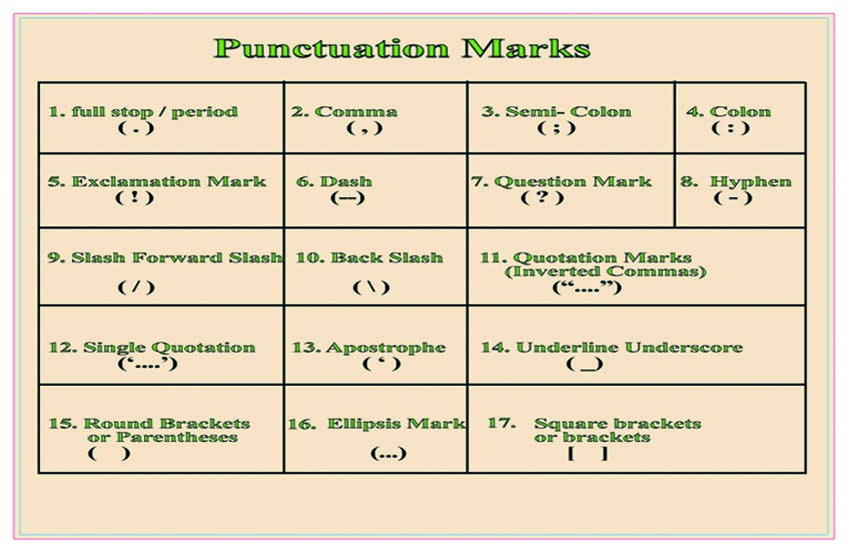

The semicolon has four major uses, as follows:

The semicolon has four major uses, as follows:

1 To link two closely related independent clauses

Jason sailed the Argos; Ahab sailed the Pequod.

2 To link clauses connected by conjunctions such as however, as a result

Ahab was consumed with the idea of vengeance against Moby Dick; as a result, he smuggled five Parsee harpooners aboard the Pequod.

3 To separate items in a list, when items within each part of the list contain commas.

The author kept her manuscript in three forms: as an electronic file, which she stored on her computer or, sometimes, on two different computers; as a paper file, which she kept in her locked file cabinet; and as a digital file, which she kept on her flash drive, which was with her at all times, even when she slept.

4 To link lengthy clauses that also contain commas, so as to distinguish between clauses.

The gardener turned the soil over twice a year, using a spade, a pitchfork, a hoe, and, finally, a rake; but she planted seeds only once, after the first turning-over.

Just as the semicolon seems a bit formal, so, too, do parentheses. As Karen Elizabeth Gordon explains in The New Well-Tempered Sentence, parentheses are meant to include additional information within a sentence — not the main information, but additional info. “They make for a softer interruption than the abrupt snapping or daring that dashes do. . . .” she explains. (Note the abruptness of that dash two sentences ago? Note the softness of this additional information?)

Gordon’s book (one of my favorite of all grammar books) is full of examples of parentheses usage. As you can see in the previous sentence, I have placed additional information within parentheses. Wisecracks, asides, insults (!), and even punctuation marks that reveal a writer’s attitude (Attitude with a capital A?) are usually placed within parentheses.

Gordon’s book (one of my favorite of all grammar books) is full of examples of parentheses usage. As you can see in the previous sentence, I have placed additional information within parentheses. Wisecracks, asides, insults (!), and even punctuation marks that reveal a writer’s attitude (Attitude with a capital A?) are usually placed within parentheses.

Brackets are called square brackets in some English-speaking countries, but in the US they’re simply called brackets. I learned about brackets in high school, probably when I was learning how to write a research paper, and I can recall using them in college papers, too. But then I began writing adult fiction and nonfiction and children’s fiction and nonfiction and also children’s activity books and filmstrips and such — and brackets disappeared from my writing.

Only to resurface again in 2010 when I wrote Research Notes for Women at Play: The Story of Women in Baseball, Volume 1. Ditto for Volume 2, which was published in 2013, and ditto for Volume 3, published in 2015.

Only to resurface again in 2010 when I wrote Research Notes for Women at Play: The Story of Women in Baseball, Volume 1. Ditto for Volume 2, which was published in 2013, and ditto for Volume 3, published in 2015.

The reason that brackets resurfaced in my writing is that one of their main uses is to enclose material added by someone other than the original author. In Research Notes I quoted a lot of original material (mainly newspaper articles from 1875-1923), and in many cases I needed to add explanatory material or indicate that something was incorrectly spelled.

In the first example below, I add the information that the Hartford referred to is in Michigan. In the second example I add a sic to indicate that the incorrectly-spelled word preceding the sic was there in the original newspaper text.

“Manager Olson has arranged for a game with Hartford [Michigan] for Friday afternoon, May 11, at the Hartford ball grounds.”

“The season has been a disasterous [sic] one to many carnivals and circuses, and with no encouraging outlook for the present season, the wise and conservative showmen will probably be in winter quarters not later than the early part of October.”

In an earlier blog I wrote that I think the apostrophe will disappear from American English sooner or later, because people simply do not understand its use to show possession. Another punctuation mark in grave danger of disappearance — it has practically vanished — is the hyphen. I often find myself confused by a billboard or ad slogan that, after three or four readings I finally figure out. Had words been properly hyphenated, I would have understood instantly. For example:

a third best vacation

a third-best vacation

The first two or three times I read the top line (which is how it appeared on a billboard), I thought somebody had taken three best vacations. Frankly, I didn’t see how that was possible. The vacations could have been good, better, best, but all three of them could not have been best. Finally I figured out that the writer meant to sneer at a particular vacation, calling it third-best. When the hyphen is missing, it takes a couple of readings to figure out exactly what is meant. (See my poem blog on the hyphen, Goodbye Hyphen, Hello Confusion.)

Here’s another example of how a missing hyphen — which is meant to join words that need to be understood as belonging together — can cause a reader to stumble.

Twice now I’ve seen the cover of a book that is titled:

BLUE EYED STRANGER

So each time I’ve seen this, I’ve read it as a blue stranger who happens to be “eyed,” and that strikes me as hilarious. The ridiculousness of the situation makes me realize that the cover designer means this to be a

BLUE-EYED STRANGER

Upon looking this book up online, I see that text descriptions (i.e., not the cover, but words) call it Blue-Eyed Stranger. So apparently it’s just the cover that is wrong. Either that, or the write-ups about the book have corrected the poor punctuation because they just couldn’t stand it!

Which is why I do not carry a pen with me.

________________

Barbara Gregorich loved using both the colon and a comma in one of her book titles — Guide to Writing the Mystery Novel: Lots of Examples, Plus Dead Bodies.

6 responses to “Punctuation Marks – 3”

Wow, this is a tough one, Lou. My gut reaction is that the exclamation mark belongs outside the quotation mark because the exclamation goes with the entire expression (just GREAT) rather than with just the word GREAT. But that is open to debate. Phil thought the exclamation went only with the word GREAT, in which case the exclamation goes inside the quote, the way you have it. The more I look at the sentence you’ve written, the more I think your punctuation is correct: that you mean to exclaim over the last word. Next time give me an easy question, please!

BTW, I think “sic” always goes in square brackets. Further, once you put quotation marks around the word “ascared”, the quotation marks indicate that you, the writer, know that you are taking liberties with standard English, so the “sic” isn’t necessary. Good luck with your nonfiction debut! I’m looking forward to it.

LikeLike

Great…just “GREAT!” Now I’ve got to go track down all the “comma splices” in my non-fiction debut (sigh).

P.S. did I put that exclamation mark in the proper position? Somehow it felt better outside the quotation mark, but now I’m to “ascared” (sic) to do that.

LikeLike

The comma splice sentence you give as an example is exactly the kind of comma splice that makes me want to scream. Re last name, I hope you guessed Croatian.

LikeLike

Barbara, thanks for replying to my most recent blog. I didn’t realize you had until I brought up our recent exchange from the “trash” file. Like you, I can accept either periods or semicolons at the ends of two short declarative sentences that are side by side, but I can’t tolerate comma splices.

Here’s an example of such a splice that I saw in the newsletter of the Rensselaer County (New York State) Historical Society a few days ago: ‘Thank you to everyone who came out this Tuesday for our #enjoytroyDeckParty, we had a blast!’

In case you’re wondering why I was reading that newsletter, i spent most of my childhood in Troy, NY, which is in Rensselaer County. Did I tell you that I’m the embodiment of Homer’s Iliad? I’m from Troy and I married Helen. My Russian wife is named Yelena, and that’s Helen in English.

With regard to the Latin word ‘sic,’ you’re right. it means ‘thus,’ and in dialogue it has the meaning of ‘yes.’ That’s where ‘si’ in Spanish, Portuguese and Italian come from; so another translation of ‘sic’ after a mistake in writing could be “Yes, he/she really said that!’

Refresh my memory. Did I ask you the ethnicity of your family name, i.e. Gregorich? As an ESL teacher, I’m always interested in something like that. I try to guess what it is before i’m told.

LikeLike

Barbara, thanks for your latest blog. i wonder how many people know the meaning of ‘sic’ and what language it is from. I also noticed that you did something that is becoming more and more common in contemporary writing: making a subordinate clause into a complete sentence. I’m referring to your sentence beginning “Only to surface with….” Another thing I’m seeing more and more of is people being afraid to write declarative sentences with only a few words. Instead of using periods, they use semicolons, as you pointed out; but they also resort to comma splices, which is a grammatically incorrect structure.

Have you ever seen the book that has the title He Eats Shoots and Leaves? It points out the difference that punctuation makes in a sentence. Contrast the title with this sentence: He eats, shoots and leaves.

i want to return to the topic of how to express possession in English. “I’m a friend of Mary’s” is considered a grammatically correct sentence in modern English; so is ‘I’m a friend of his.’ Here you have both possessive constructions side by side. ‘I’m a friend of Mary’s’ literally means “i’m a friend of Mary of Mary.’ ‘I’m a friend of his’ literally means ‘I’m a friend of him of him.’ My guess is that a mistake became the rule, much like ‘It’s me’ supplanting ‘It is I.’ Comments?

LikeLike

Wow, lots to reply to here! I know that “sic” comes from Latin and I think it means “thus,” and I suspect that “sic” within brackets stands for a longer Latin expression, but I don’t know what that expression is. “Thus was it written?” ”

Yes, I feel free to use subordinate clauses as full sentences, and that probably comes from being a writer of fiction (where, probably, more liberties are taken with language than are taken in nonficiton) and/or writing in modern media, where even greater liberties are taken. When I write a fragment, I do it for emphasis and rhythm and sometimes for humor.

I haven’t noticed that short declarative sentences are fewer than they used to be. I like short sentences and I tend to avoid sentences punctuated with semicolons. If this is, as you say, a trend, then it’s an interesting one. In my opinion, semicolons tend to make a piece of writing look too formal and too dull. Sprinkle generously with periods, question marks, and dashes to lighten up the look. As to comma splices, I occasionally use them deliberately in fiction, in dialogue to indicate a kind of non-stop talking. In some dialogue a semicolon would convey the wrong message, and a period would slow things down too much. However, I try to NEVER use a comma splice in nonfiction.

Indeed, I have read and enjoyed “Eats Shoots and Leaves.” If I recall, she is particularly hard on all the misuse of the apostrophe. Which brings me to your last point, the misuse of the apostrophe for possession. I am guilty of speaking phrases such as “I’m a friend of Mary’s,” and perhaps even of writing them in dialogue, but up until you pointed it out, I never thought about what this means. I suspect you’re right, that this common usage is now the norm. There’s no going back on it. Ditto for “it’s me,” at least in informal English.

Thanks for all the interesting observations!

LikeLike