From my earliest childhood days, I was a fan of cowboys. I wore Stetsons and toted cap-gun sixshooters and never traveled far from the ranch without a BB rifle slung over my shoulders. When I wasn’t rounding up the cattle or stringing barbed wire I strummed the banjo, one of those plastic windups that played one tune: “Home on the Range.” I would have preferred “The Old Chisholm Trail,” but cowboys don’t complain. By the time I was eight years old, I had selected the greatest cowboy song of all time and learned its lyrics. I can still recite them today.

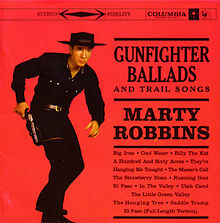

That song was “The Strawberry Roan” as sung by Marty Robbins on Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs. With lyrics by Curely Fletcher, the song has a few different versions — but a comparison clearly shows that the simplest, most memorable, and most dramatic version (cutting away all the clutter) is the Marty Robbins version.

Somewhere around the age of ten I abandoned my cowboy gear. But I never abandoned “The Strawberry Roan,” and now, decades later, I recognize that, had anybody been placing bets on what I would become when I grew up, they would not have bet “cowgirl.” The wisest among them would have bet “writer.”

Somewhere around the age of ten I abandoned my cowboy gear. But I never abandoned “The Strawberry Roan,” and now, decades later, I recognize that, had anybody been placing bets on what I would become when I grew up, they would not have bet “cowgirl.” The wisest among them would have bet “writer.”

They would have bet that way because the song I was attached to like a burr to a saddle blanket was a song with a strong, clear dramatic structure , much like the structure of a novel, play, or movie. In five eight-line stanzas, the lyrics take us from defeat to seeming victory to defeat-with-knowledge. A complete story cycle, with dramatic rising action.

In the first stanza we learn that a bronc fighter, out of a job, is approached by a stranger who needs a horse tamer. But the stranger warns the cowboy that the horse in question has had a lot of luck throwing good riders.

This warning only inflames the cowboy, who “gets all het up”,” speaks ill of the “nag” in question, and brags that he can beat any horse alive. By the end of the second stanza we’re out at the ranch, where the cowboy hero will get a look at the horse he has been hired to tame.

Seven of the eight lines of the third stanza describe the strawberry roan in great detail. He sounds like a wreck: old, his hocks swollen, pigeon-toed, u-necked. The listener is amused and lulled by this highly descriptive information which makes the roan seem no threat at all. And then comes the eighth line, the reversal, when the cowboy, wise in the ways of horses, reveals that Strawberry is “a regular outlaw.”

So three-fifths of the way into the story we have met the protagonist and antagonist and we understand the conflict. One of these two will win, Cowboy or Strawberry. The confrontation will be neither pleasant nor easy.

In the fourth stanza we’re let in on the fact that the cowboy, mounting the strawberry roan, recognizes the severity of what he faces. The instant the cowboy steps in the saddle and releases the blind, Strawberry reacts, frog-walking, twisting, bucking, heaving, and, at the end of the stanza, turning his belly toward the sun. (Putting his head low between his front legs while kicking his hind legs as high as he can.) Horse and rider, as well as listener/reader, are left suspended in the air as the fourth stanza ends.

Strawberry comes back to earth hard. Then up he bucks again, this time dislodging the defeated cowboy, who hyperbolically spins twice before hitting the ground. The final stanza is followed by a three-line summary in which the cowboy admits defeat and argues that no man alive could ride the strawberry roan.

As a kid, I loved that ending, mainly because I wanted Strawberry to win the contest. But I also loved the ending because I recognized that the cowboy was, throughout the song, engaging in humor at his own expense. The humor served to make the cowboy a mere mortal while elevating Strawberry to a higher level: The Horse That Couldn’t Be Broken.

There, in one short song, are the main elements of story — setting, challenge, protagonist and antagonist, conflict, rising action (literal as well as figurative!), climax, and change. No wonder I unsaddled my pony, hung up my sixshooters, kicked off my spurs, and became a writer.

5 responses to “The Strawberry Roan”

I liked Zorro, too: fighter against injustice. I never carried a sword, though, or wore a cape. Or mask. At one time I tried flipping a whip, a la Lash LaRue. The whip proved much too difficult to master: I ended up flicking myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ma’am, you sure do spin a great yarn (and a great simile :)! Personally, my cowbow days were slim pickin’s. However, I was big into Zorro. Guess that’s why I carved his name into my mom’s new dining room table! Thanks for the great analogy Barbara, very nice. And the u-tube video James (was that a Hee Haw episode)? But can someone explain how the heck Mary Robbins was playing the guitar while it was hanging from one hand (yuk, yuk)! Ciao Lou

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this song but never thought about its structure before.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m happy that you got to listen to the Marty Robbins version again, after all this time.

LikeLike

I remember loving that song as a kid, too, although I had only a very vague idea what a ‘roan’ was, and the image in my head of what a ‘strawberry roan’ might look like was even more confused. I did know what a strawberry looked like, but it didn’t seem to help much. I had to find a YouTube of it, and the Marty Robbins one was the version I listened to for the last time fifty years ago, without a doubt.

LikeLiked by 1 person